“Lies, Damned Lies And Statistics”. Understand The Problem Through Research And The Publishing Of Meaningful Data

December 20, 2021

In around 2014, I attended an event at the London School of Economics at which I was invited to talk about issues arising in the case of DSD & NBV v Commissioner of Police for the Metropolis. This was the case brought by two of the victims of serial rapist taxi driver John Worboys. It led to a landmark judgment as it established that the police had a duty under Article 3 ECHR to adequately investigate serious crimes of violence committed by members by third parties, including rape. Worboys had drugged and raped over 100 women over a six-year period and continued to get away with it because of police failures in the investigation of a number of cases where women reported him. The invitation came from Professor Elizabeth Stanko, a criminologist, who had spent the previous ten years embedded in the Metropolitan police analysing the reported rape cases and their outcomes following an investigation. Her analysis chimed in with what we had found in the DSD case, namely that a very small proportion of reported rapes resulted in a charge. She broke down the data comparing outcomes for victims depending on a range of different characteristics. The most disturbing aspect of her data showed that cases involving victims with learning difficulties or mental health problems were virtually never prosecuted.

The publication of data informs any issue or problem in society and helps direct policy and action. We see that every day with the Covid reporting and not infrequently over the last year have we seen the publication of statistics and evidence showing the prevalence of rape, domestic violence, police perpetrated abuse and other forms of violence against women, set against the dismal outcomes in police investigation and prosecution. This in turn has led to demands for action and new commitments to tackling the problem. But we know statistics can tell only a part of the story and often they hide just as much as they tell us.

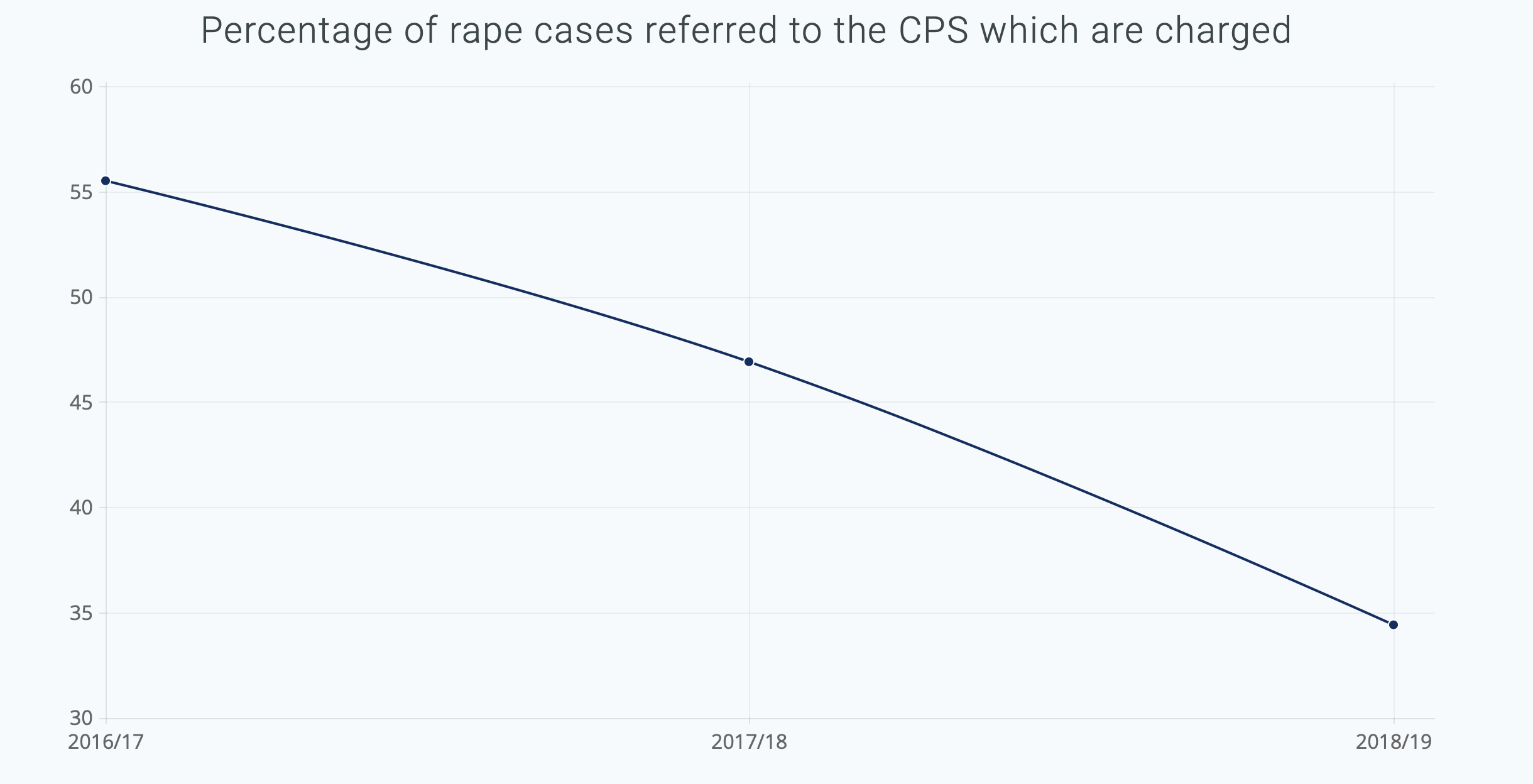

On 10 July 2020 Gregor McGill, Director of Legal Services at the CPS gave evidence at the Independent Inquiry on Child Sexual Abuse (IICSA) where he said, “My experience is that we are more successful in prosecuting these cases than we have ever been“. At that time CWJ were in the midst of the historic legal challenge that we were bringing on behalf of the End Violence Against Women coalition against the Director of Public Prosecutions in relation to the collapse in the prosecution of rape over the past few years. (There has been a similar collapse in relation to other sexual offending including child sexual abuse). In the case, we argued that it was the CPS and in particular Gregor McGill who had led on training and amendments to published guidance on the prosecution of rape which was the primary cause in the fall in the volume of rape cases being prosecuted.

I wrote to IICSA highlighting the potentially misleading evidence provided by McGill, pointing out and relying on evidence from our case which showed that:

Yr

2016/17

2017/18

2018/19

Cases referred to CPS

6661

6012

5114

Cases charged

3671 (55.5%)

2822 (46.9%)

1758 (34.4%)

This amounted to a fall of 52% of rape cases charged in two years. And viewed against a 173% increase in reports made to the police between 2014 and 2018.

We were made aware of McGill’s evidence because at the time we were a core participant in a different strand of the inquiry examining child sexual exploitation by organised networks. The dominant narrative in the media relating to this issue was that it was all about Asian grooming gangs targeting white girls. Despite this, the Inquiry had chosen not to explore this issue in any detail and there was minimal evidence produced to question this narrative. We therefore obtained witness evidence from two specialist women’s services for black and minoritised victims of abuse and exploitation.

Zlaka Ahmed from Apna Haq, a Rotherham based specialist ‘by and for’ group supporting women escaping violence, gave evidence highlighting the number of young mainly Asian girls who were targeted by the gangs operating in that area and Rosie Lewis from the Angelou Centre (based in the North East) highlighted how racist policing led to the criminalisation of a black girl who was being sexually exploited. Both witnesses highlighted how important it is for criminal justice agencies including the CPS to collect meaningful data that is disaggregated as to sex and as to intersecting oppressions. To quote Rosie in the evidence she gave,

“there is a disproportionate focus on 'saying the right thing' in a race-based analysis of C/SE, without approaching it from a gender-based analysis. The fact that perpetrators are often viewed as particular communities, but not generally seen as men, is problematic, as the reality is the vast majority of perpetrators are men.”

In CWJ’s Women who Kill report published this year we identified that over a ten-year period from April 2008 to March 2018, 108 men were killed by women with whom they had been in a relationship (either at the time of the killing, or previously). In comparison, nearly eight times as many women (n=840) were killed by partners or ex-partners during the same period. Whilst this tells us that many more men kill women than women kill men (by 8 to 1 ratio), it doesn’t set out the underlying context for these homicides. The research explores in detail from a range of primary and secondary data women’s journey through the criminal justice system. What we found from this in-depth analysis is that in the vast majority of cases where women who killed their partners, there was a history of previous violence and abuse from the man towards them.

In contrast, the femicide census which last year published a report on women killed by men between 2009 and 2018, found that. “a history of prior abuse of the victim by the perpetrator was evident in at least 611 cases, constituting 59% of 1,042 femicides committed by intimate partners”.

The crime survey for England and Wales for the year ending in 2019, reports that an estimated 7.5% of women (1.6 million) and 3.8% of men (786,000) experienced domestic abuse in the last year. That statistic might be used to show that while women are more likely than men to be victims, there is not a very wide disparity. However, as I highlighted in part 3 of this manifesto on the criminalisation of victims of abuse, male perpetrators often make counter allegations when the police are called and too often the woman is arrested because of a failure to explore the underlying context of the abuse. We also know that when we drill down further into reports that women are far more likely to experience multiple incidents of abuse and more serious forms of abuse including, in particular, sexual violence.

We need to ensure when we look at violence and abuse that we understand who the victims are and who are the perpetrators and how victims with intersecting oppressions can be disproportionately targeted. This is important for so many reasons, not least because it has huge implications for policy approaches in tackling the issue and for resourcing of support services.